I began sculpting in the south of France, in the heart of the Alpilles, with my mentor Costa Coulentianos. After initially learning to sculpt metal, I gradually evolved towards creations that aligned with my commitment to nature. Here are a few selected works from this journey.

Solar Fountain

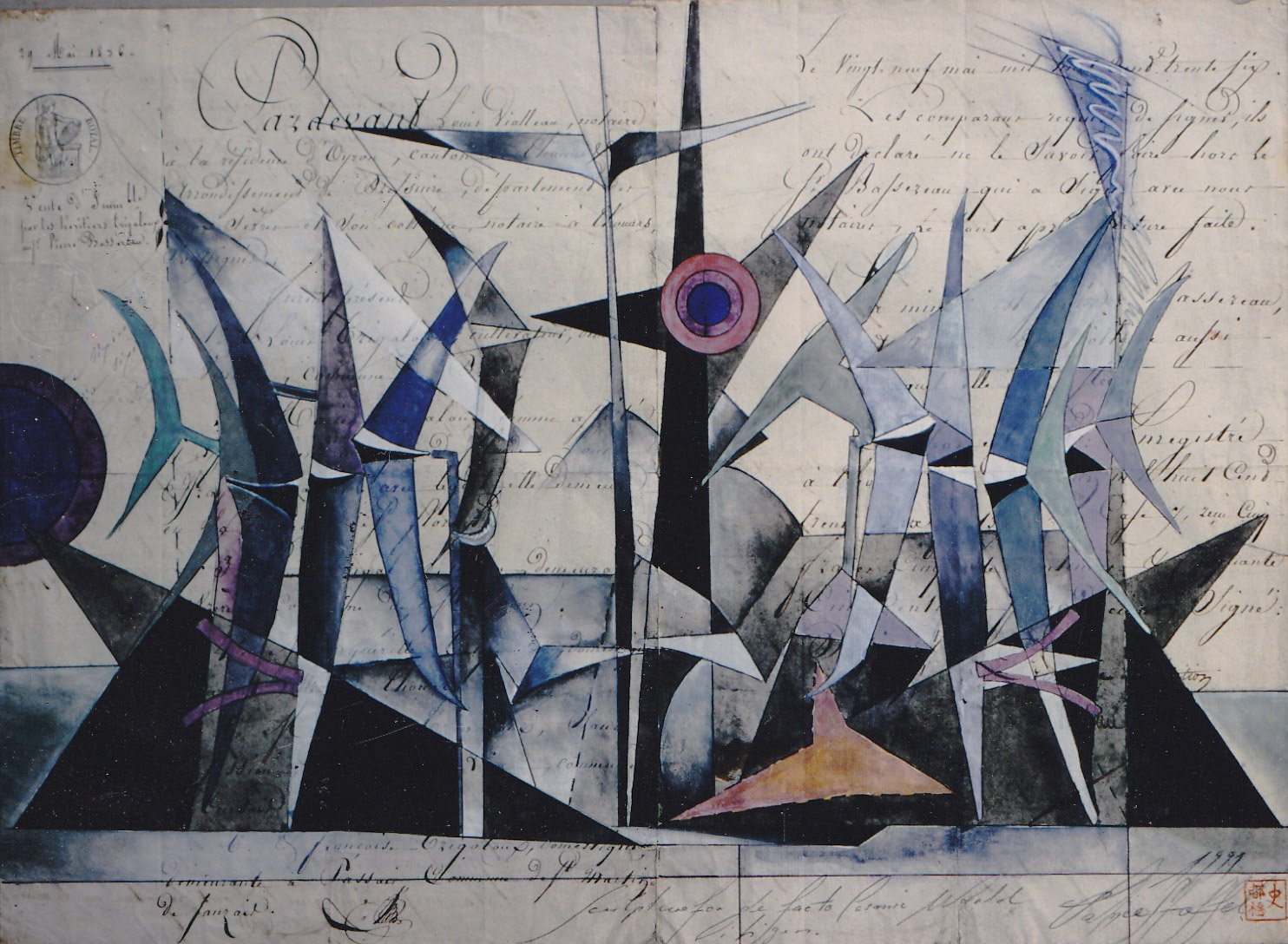

Fontaine Solaire, Cosmica by Patrice Stellest stands as a pivotal work in the artist’s journey, marking the transition between his exploration of cosmic art and his commitment to a symbiosis with nature. This drawing, both complex and visionary, outlines the contours of a shift towards a new form of artistic expression where technology and nature coexist harmoniously.

The composition is dominated by sharp and dynamic geometric shapes, evoking futuristic architectural structures while retaining an organic fluidity. These shapes, reminiscent of bursts of light or crystals, symbolize solar energy, the central element of the envisioned fountain. The choice of these forms, both rigid and elegant, illustrates the fusion of nature and technology, a recurring theme in Stellest’s work. They reflect controlled, channeled energy that remains alive, ready to fuel creation and support a perpetual movement.

The colors used, mainly shades of blue, violet, and black, give the work a cosmic dimension, recalling the vastness of the universe while staying grounded in a terrestrial reality. These hues create a play of shadows and lights that bring the composition to life, suggesting the shimmering of water under sunlight, a fundamental element of the solar fountain imagined by Stellest.

The fountain itself, though represented abstractly, is distinguished by a harmonious arrangement of its components. It seems to rise from the paper, ready to spring forth and fulfill its role as a source of perpetual water. This idea of a constant flow, an unbroken energy, is materialized through the repeated use of circular motifs and ascending lines, symbolizing both the movement of water and an ascent towards a higher consciousness.

Beyond its aesthetic appeal, this drawing embodies a deeply philosophical vision: that of art no longer being merely contemplative, but interacting with its environment, drawing strength from nature while respecting its balance. The solar fountain here becomes a metaphor for this interaction, a model of sustainability where natural energy is used to create a self-sustaining cycle of life.

By integrating solar energy into the work, Stellest takes a bold step towards what he calls “art with nature,” a concept that goes beyond mere representation to embrace a true collaboration between humans and the environment. Fontaine Solaire, Cosmica is therefore more than a drawing; it is a visual manifesto for a future where art, technology, and nature converge to create something new, perpetual, and deeply harmonious.

This work heralds Stellest’s future developments, as he continues his quest for balance between natural forces and human expression, always guided by a cosmic vision of humanity’s place in the universe.

The composition is dominated by sharp and dynamic geometric shapes, evoking futuristic architectural structures while retaining an organic fluidity. These shapes, reminiscent of bursts of light or crystals, symbolize solar energy, the central element of the envisioned fountain. The choice of these forms, both rigid and elegant, illustrates the fusion of nature and technology, a recurring theme in Stellest’s work. They reflect controlled, channeled energy that remains alive, ready to fuel creation and support a perpetual movement.

The colors used, mainly shades of blue, violet, and black, give the work a cosmic dimension, recalling the vastness of the universe while staying grounded in a terrestrial reality. These hues create a play of shadows and lights that bring the composition to life, suggesting the shimmering of water under sunlight, a fundamental element of the solar fountain imagined by Stellest.

The fountain itself, though represented abstractly, is distinguished by a harmonious arrangement of its components. It seems to rise from the paper, ready to spring forth and fulfill its role as a source of perpetual water. This idea of a constant flow, an unbroken energy, is materialized through the repeated use of circular motifs and ascending lines, symbolizing both the movement of water and an ascent towards a higher consciousness.

Beyond its aesthetic appeal, this drawing embodies a deeply philosophical vision: that of art no longer being merely contemplative, but interacting with its environment, drawing strength from nature while respecting its balance. The solar fountain here becomes a metaphor for this interaction, a model of sustainability where natural energy is used to create a self-sustaining cycle of life.

By integrating solar energy into the work, Stellest takes a bold step towards what he calls “art with nature,” a concept that goes beyond mere representation to embrace a true collaboration between humans and the environment. Fontaine Solaire, Cosmica is therefore more than a drawing; it is a visual manifesto for a future where art, technology, and nature converge to create something new, perpetual, and deeply harmonious.

This work heralds Stellest’s future developments, as he continues his quest for balance between natural forces and human expression, always guided by a cosmic vision of humanity’s place in the universe.

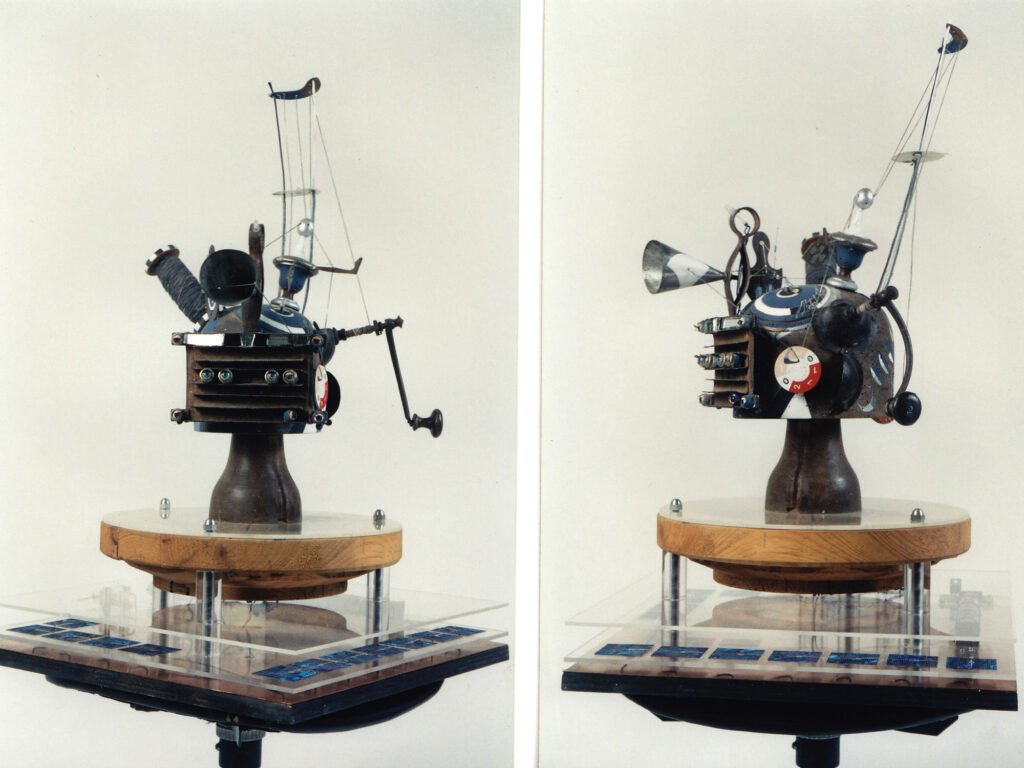

Solar Head

Born from a collaboration with physicist Bernard Gitton, Patrice Stellest’s sculpture Solar Head is a visionary work that crystallizes the interaction between art, technology, and nature. Created in the early 1990s, it stands as an emblematic figure from a time when solar energy, still nascent, represented a promising yet distant technological dream. Stellest, in a gesture both poetic and bold, captures this utopia and translates it into a tangible, almost living work.

This sculpture, made from a variety of materials—wood, metal, electronic circuits—seems to evoke a head, a helmet, or a futuristic bust. Its lines are both robust and organic, suggesting a hybrid between human and machine, a vision where the two coexist harmoniously. The geometric shapes, painted in black, white, and blue, recall the abstract motifs of constructivism, but here they are reappropriated to express a new energy, that which is harnessed from the sun.

What makes Solar Head particularly captivating is its functional character. Equipped with solar panels and blue LED lights, it recharges during the day to illuminate throughout the night, like a sparkling tree, like a firefly. This ability to transform sunlight into visible energy at night makes it a kinetic work, in perpetual interaction with its environment.

The elements of the sculpture, such as taut cables, disks, and coils, evoke mechanisms both ancient and futuristic, as if Stellest had drawn from an imaginary past to anticipate a future in balance with nature. The sculpture’s solid and circular base supports this complex ensemble, accentuating the idea of anchorage and connection to the earth.

The phone conversation between Stellest and surrealist photographer Dora Maar, shortly before her death, adds an emotional dimension to this work. Maar’s fascination with the concept of the Solar Head testifies to the timeless appeal of this sculpture, which transcends generations and artistic movements.

In sum, Solar Head is an ode to sustainable innovation, a testament to the ability of art to draw upon technological advances while remaining deeply rooted in a reflection on the interaction between humanity and its environment. With this sculpture, Stellest does not merely represent an idea; he materializes it, makes it tangible, and, above all, brings it to life.

This sculpture, made from a variety of materials—wood, metal, electronic circuits—seems to evoke a head, a helmet, or a futuristic bust. Its lines are both robust and organic, suggesting a hybrid between human and machine, a vision where the two coexist harmoniously. The geometric shapes, painted in black, white, and blue, recall the abstract motifs of constructivism, but here they are reappropriated to express a new energy, that which is harnessed from the sun.

What makes Solar Head particularly captivating is its functional character. Equipped with solar panels and blue LED lights, it recharges during the day to illuminate throughout the night, like a sparkling tree, like a firefly. This ability to transform sunlight into visible energy at night makes it a kinetic work, in perpetual interaction with its environment.

The elements of the sculpture, such as taut cables, disks, and coils, evoke mechanisms both ancient and futuristic, as if Stellest had drawn from an imaginary past to anticipate a future in balance with nature. The sculpture’s solid and circular base supports this complex ensemble, accentuating the idea of anchorage and connection to the earth.

The phone conversation between Stellest and surrealist photographer Dora Maar, shortly before her death, adds an emotional dimension to this work. Maar’s fascination with the concept of the Solar Head testifies to the timeless appeal of this sculpture, which transcends generations and artistic movements.

In sum, Solar Head is an ode to sustainable innovation, a testament to the ability of art to draw upon technological advances while remaining deeply rooted in a reflection on the interaction between humanity and its environment. With this sculpture, Stellest does not merely represent an idea; he materializes it, makes it tangible, and, above all, brings it to life.

Thomas Kellner

Stellephant

Stellephant, by Patrice Stellest, is a sculpture created with physicist Bernard Gitton, standing as a monument that is both critical and poetic: an ensemble of four symbolic towers confronting us with the brutality of history, environmental destruction, and the unwavering resistance of nature.

An Assemblage of Stories and Sorrows

The sculpture consists of four slender towers, each stretching towards the sky as if rising above the weight of the history it carries. These towers, constructed from eclectic but carefully selected objects, tell the story of colonial violence, ruthless hunting, and the suffering of living beings, while highlighting a nature that, though devastated, refuses to be silent.

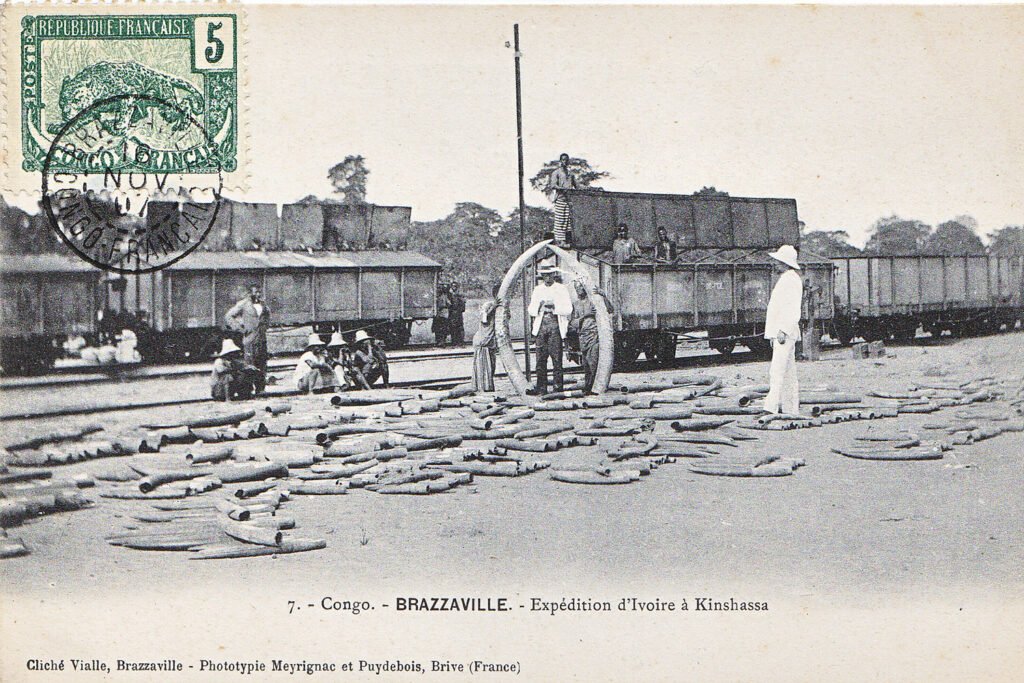

Tower #1: The Burden of the Past

The first tower, with its suitcases attached to a hand truck, accumulates rifles and other hunting-related objects, evoking the equipment of elephant hunters from the last century. These suitcases, heavy with history, symbolize the burden of colonization, where elephants were merely resources to be exploited, their tusks becoming trophies or aphrodisiacs, especially prized in Asia. The tower becomes a critique of this human greed, where desire and domination justified the destruction of majestic species. The accumulated objects, like relics from a bygone era but still present in our consciousness, remind us that this exploitation continues, revived by new forms of economic colonialism.

Tower #2: Forced Migration

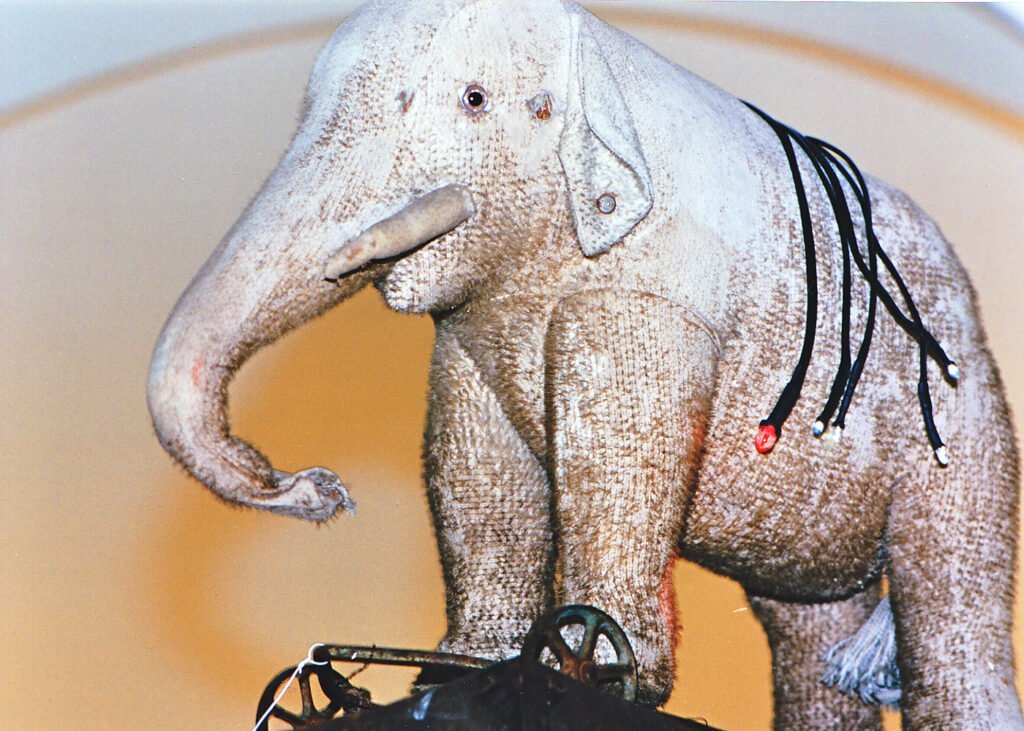

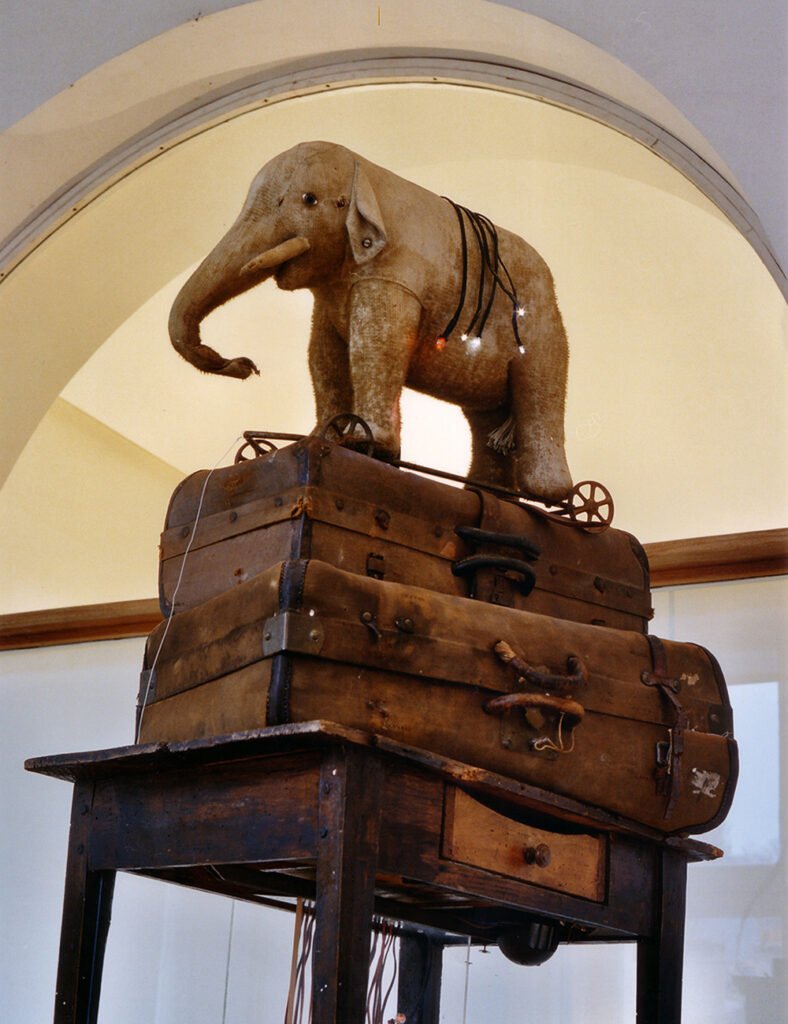

At the top of the second tower, an elephant—the “Stellephant”—stands atop two suitcases, themselves placed on a very high table. This powerful image is a metaphor for elephants who, like indigenous peoples, have been forced to migrate, to leave their lands for reserves where their existence is confined. The suitcases evoke both travel and exile, a state of constant displacement, never truly able to settle. The Stellephant, the central figure of the sculpture, represents not only this forced exile but also the dignity and resilience of those who, though marginalized, continue to fight for survival. The growing aggression of elephants towards humans in recent years is symbolized here as a desperate response to the encroachment on their territories.

Tower #3: The Memory of Violence

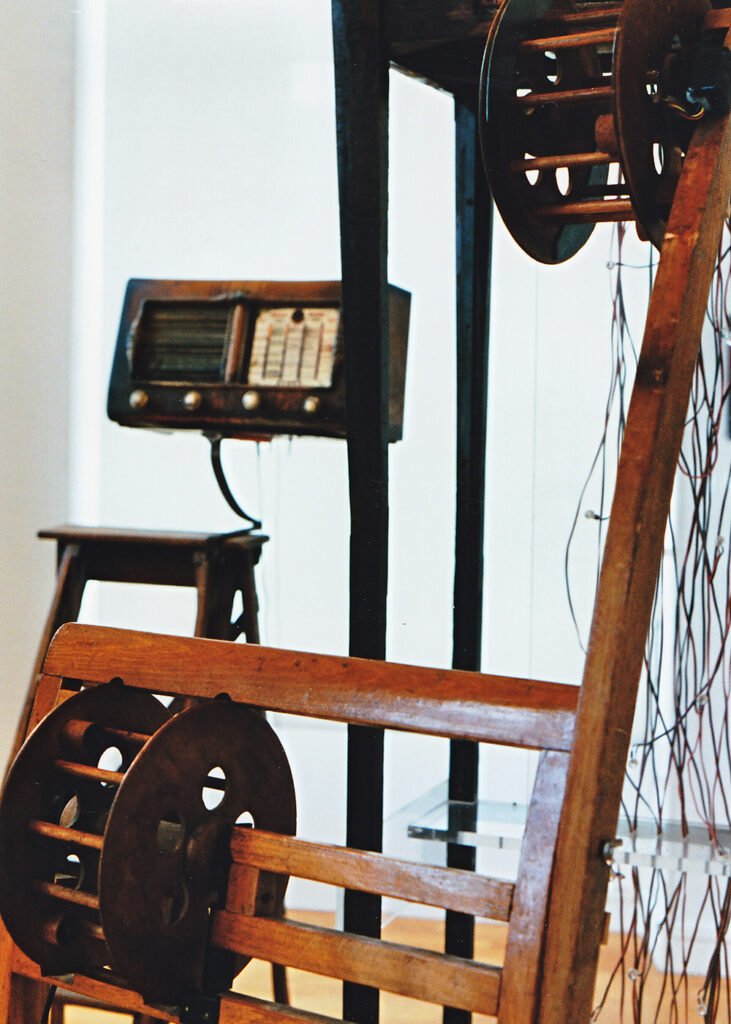

The third tower, with its World War II interrogation chair, introduces an element of more direct violence. The rotating wheels, which activate highly sensitive microphones, are metaphors for memory, for how acts of violence are recorded, captured, but also distorted over time. The chair, an instrument of torture and submission, becomes here the seat of a painful memory, where each turn of the wheel, each captured sound, is a reminder of human cruelty. This tower suggests that the violence inflicted on nature is also violence inflicted on our own humanity, a violence that leaves indelible marks.

Tower #4: The Cry of Revolt

The fourth tower reanimates the captured sounds, transforming them into a cry of revolt emanating from the Stellephant. The recorded sound waves are reactivated by an old radio, giving the elephant the power to trumpet, to be heard, to assert its right to exist. This cry, amplified by technology, becomes a metaphor for the resistance of nature, a nature that will not allow itself to be annihilated without expressing its suffering. The 1930s radio, with its aged and worn appearance, symbolizes the persistence of these voices, these cries, across ages, like an echo that refuses to disappear.

An Interactive and Engaging Work

Stellephant is not merely a sculpture to be observed; it is a work that actively engages the viewer. The red diodes, reanimated sounds, familiar but transformed objects—everything in this sculpture is designed to provoke, to make the observer pause and reflect. Stellest uses assemblage not to create a simple collage of objects, but to construct a complex and immersive narrative that spans ages and cultures. It is a sharp critique of the colonial legacy, a reflection on humanity’s place in nature, and a call for collective responsibility to preserve what remains of our natural world.

Thus, Stellephant is a work anchored in the past and oriented towards the future, a work that reminds us that the struggle for nature’s survival is also a struggle for our humanity’s survival. Stellest combines his ecological concern with artistic mastery, making this sculpture a living fresco, a monument to the silent yet powerful resistance of elephants, and by extension, all of nature.

An Assemblage of Stories and Sorrows

The sculpture consists of four slender towers, each stretching towards the sky as if rising above the weight of the history it carries. These towers, constructed from eclectic but carefully selected objects, tell the story of colonial violence, ruthless hunting, and the suffering of living beings, while highlighting a nature that, though devastated, refuses to be silent.

Tower #1: The Burden of the Past

The first tower, with its suitcases attached to a hand truck, accumulates rifles and other hunting-related objects, evoking the equipment of elephant hunters from the last century. These suitcases, heavy with history, symbolize the burden of colonization, where elephants were merely resources to be exploited, their tusks becoming trophies or aphrodisiacs, especially prized in Asia. The tower becomes a critique of this human greed, where desire and domination justified the destruction of majestic species. The accumulated objects, like relics from a bygone era but still present in our consciousness, remind us that this exploitation continues, revived by new forms of economic colonialism.

Tower #2: Forced Migration

At the top of the second tower, an elephant—the “Stellephant”—stands atop two suitcases, themselves placed on a very high table. This powerful image is a metaphor for elephants who, like indigenous peoples, have been forced to migrate, to leave their lands for reserves where their existence is confined. The suitcases evoke both travel and exile, a state of constant displacement, never truly able to settle. The Stellephant, the central figure of the sculpture, represents not only this forced exile but also the dignity and resilience of those who, though marginalized, continue to fight for survival. The growing aggression of elephants towards humans in recent years is symbolized here as a desperate response to the encroachment on their territories.

Tower #3: The Memory of Violence

The third tower, with its World War II interrogation chair, introduces an element of more direct violence. The rotating wheels, which activate highly sensitive microphones, are metaphors for memory, for how acts of violence are recorded, captured, but also distorted over time. The chair, an instrument of torture and submission, becomes here the seat of a painful memory, where each turn of the wheel, each captured sound, is a reminder of human cruelty. This tower suggests that the violence inflicted on nature is also violence inflicted on our own humanity, a violence that leaves indelible marks.

Tower #4: The Cry of Revolt

The fourth tower reanimates the captured sounds, transforming them into a cry of revolt emanating from the Stellephant. The recorded sound waves are reactivated by an old radio, giving the elephant the power to trumpet, to be heard, to assert its right to exist. This cry, amplified by technology, becomes a metaphor for the resistance of nature, a nature that will not allow itself to be annihilated without expressing its suffering. The 1930s radio, with its aged and worn appearance, symbolizes the persistence of these voices, these cries, across ages, like an echo that refuses to disappear.

An Interactive and Engaging Work

Stellephant is not merely a sculpture to be observed; it is a work that actively engages the viewer. The red diodes, reanimated sounds, familiar but transformed objects—everything in this sculpture is designed to provoke, to make the observer pause and reflect. Stellest uses assemblage not to create a simple collage of objects, but to construct a complex and immersive narrative that spans ages and cultures. It is a sharp critique of the colonial legacy, a reflection on humanity’s place in nature, and a call for collective responsibility to preserve what remains of our natural world.

Thus, Stellephant is a work anchored in the past and oriented towards the future, a work that reminds us that the struggle for nature’s survival is also a struggle for our humanity’s survival. Stellest combines his ecological concern with artistic mastery, making this sculpture a living fresco, a monument to the silent yet powerful resistance of elephants, and by extension, all of nature.

Thomas Kellner

Stelleshoes

Stelleshoes by Patrice Stellest is a mechanical kinetic sculpture that transcends mere functionality to become a complex allegory of humanity in motion, a reflection on the passage of time and the persistence of cultural traditions across generations. This work is the result of a rich and varied collaboration, combining the ingenuity of physicist-artist Bernard Gitton, the craftsmanship of his assistant Sylvain Chabouty, and the personal history of Conchita, a Hungarian aristocrat who had to rebuild her life after the Soviet invasion of Hungary.

A Collection of Stories in Motion

At the heart of Stelleshoes lies an eclectic collection of shoes, each carrying a story, a culture, an era. The red Chinese dance shoes found in New York, the white wedding shoes from Los Angeles, and the shoe molds from Italy, France, and Belgium form a mosaic of cultural narratives. Each shoe, each mold, embodies a generation, a tradition that continues to move forward, to walk through time, symbolizing humanity in perpetual evolution.

These shoes are not simply displayed; they are animated. When the viewer sits on the finely sculpted metal seat and begins to pedal, they activate a complex mechanism—a unique pedal system made by Singer at the beginning of the century. This movement transfers mechanical force to the shoes, which then begin to walk. This simple act transforms the sculpture into an interactive experience, directly engaging the viewer in the creative process. The sound of the shoes walking, recreating the noise of steps, dances, and shared moments of joy, becomes a living soundtrack that accompanies the contemplation of the work.

Symbolism and Collaboration

The collaboration between Stellest, Gitton, Chabouty, and Conchita adds an extra dimension to the work, uniting science, art, and personal memory. Gitton, with his expertise in physics and mechanics, brings scientific precision to the sculpture, while Conchita, with her story of resilience and adaptation, infuses a human depth into the work. Their contribution makes Stelleshoes a work that goes beyond the boundaries of art to engage in a broader reflection on the human condition.

The choice of materials—wood, metal, and reclaimed objects—adds rich texture to the sculpture, reinforcing the idea that humanity is shaped by the objects and memories it preserves. The presence of the wooden radio atop the shoe cabinet suggests a connection between past and present, a link between the voices of the past and the steps of today.

A Journey Through Time

Stelleshoes is a meditation on movement and continuity. The shoes, ordinary objects, here become vectors of a poetic exploration of time and memory. Walking in place, they remind us that time never stops, that each generation leaves a footprint, even as it seems to blend into the next. The shoes, which have traveled across continents and eras, embody the stories of those who wore them—the hopes, joys, and sorrows of those who have moved forward, sometimes against all odds, toward an uncertain future.

By pedaling, the viewer becomes part of this story, a link in the unbroken chain of time. The sound of the shoes resonating in the space recalls the echoes of the past that follow us, even as we move towards the future.

A Living and Engaging Sculpture

Ultimately, Stelleshoes is not just a sculpture to be observed but a work to be experienced, to be lived. It invites us to reflect on our place in the continuum of time, on the traditions we carry, on the stories we pass on. Through its direct interaction with the viewer, it becomes a mirror of our own humanity, reminding us that every step counts, that every movement contributes to building a collective legacy.

Stellest thus manages to create a work that is both intimate and universal, personal and collective. Stelleshoes is an ode to humanity in motion, a celebration of the passage of time and the resilience of cultures through the ages.

A Collection of Stories in Motion

At the heart of Stelleshoes lies an eclectic collection of shoes, each carrying a story, a culture, an era. The red Chinese dance shoes found in New York, the white wedding shoes from Los Angeles, and the shoe molds from Italy, France, and Belgium form a mosaic of cultural narratives. Each shoe, each mold, embodies a generation, a tradition that continues to move forward, to walk through time, symbolizing humanity in perpetual evolution.

These shoes are not simply displayed; they are animated. When the viewer sits on the finely sculpted metal seat and begins to pedal, they activate a complex mechanism—a unique pedal system made by Singer at the beginning of the century. This movement transfers mechanical force to the shoes, which then begin to walk. This simple act transforms the sculpture into an interactive experience, directly engaging the viewer in the creative process. The sound of the shoes walking, recreating the noise of steps, dances, and shared moments of joy, becomes a living soundtrack that accompanies the contemplation of the work.

Symbolism and Collaboration

The collaboration between Stellest, Gitton, Chabouty, and Conchita adds an extra dimension to the work, uniting science, art, and personal memory. Gitton, with his expertise in physics and mechanics, brings scientific precision to the sculpture, while Conchita, with her story of resilience and adaptation, infuses a human depth into the work. Their contribution makes Stelleshoes a work that goes beyond the boundaries of art to engage in a broader reflection on the human condition.

The choice of materials—wood, metal, and reclaimed objects—adds rich texture to the sculpture, reinforcing the idea that humanity is shaped by the objects and memories it preserves. The presence of the wooden radio atop the shoe cabinet suggests a connection between past and present, a link between the voices of the past and the steps of today.

A Journey Through Time

Stelleshoes is a meditation on movement and continuity. The shoes, ordinary objects, here become vectors of a poetic exploration of time and memory. Walking in place, they remind us that time never stops, that each generation leaves a footprint, even as it seems to blend into the next. The shoes, which have traveled across continents and eras, embody the stories of those who wore them—the hopes, joys, and sorrows of those who have moved forward, sometimes against all odds, toward an uncertain future.

By pedaling, the viewer becomes part of this story, a link in the unbroken chain of time. The sound of the shoes resonating in the space recalls the echoes of the past that follow us, even as we move towards the future.

A Living and Engaging Sculpture

Ultimately, Stelleshoes is not just a sculpture to be observed but a work to be experienced, to be lived. It invites us to reflect on our place in the continuum of time, on the traditions we carry, on the stories we pass on. Through its direct interaction with the viewer, it becomes a mirror of our own humanity, reminding us that every step counts, that every movement contributes to building a collective legacy.

Stellest thus manages to create a work that is both intimate and universal, personal and collective. Stelleshoes is an ode to humanity in motion, a celebration of the passage of time and the resilience of cultures through the ages.

Thomas Kellner

Hello Dolly TV

Hello Dolly TV by Patrice Stellest explores themes of technological alienation and mass manipulation, while confronting the viewer with a sharp reflection on the impact of media and scientific advances on contemporary society.

This sculpture, created in Candes Saint Martin with the collaboration of physicist-artist Bernard Gitton, combines elements of popular culture and everyday objects, transformed into critical symbols of an era marked by the industrialization of knowledge and the endless repetition of images. The central piece, an old yellow Bakelite television from the 1960s, stands as a relic from a time when technology was still perceived as a promise of a bright future. However, this television, now defective and obsolete, becomes a dystopian vehicle: the images it broadcasts are endless, creating a hypnotic loop that simulates the passive and numbing experience of media consumption.

In front of this screen, a dilapidated lounge chair, covered in drippings à la Jackson Pollock, suggests a human presence reduced to the state of a passive spectator. The paint flowing on the chair recalls both free artistic expression and the underlying chaos of modernity, contrasting with the control and repetition symbolized by the television.

The polyurethane head of a “pre-cloned” man attached to the chair’s back is a direct nod to the landmark event of the first sheep cloning, Dolly. This reference to cloning is not only biological but also ideological: the work denounces the standardization of thoughts and behaviors, a phenomenon exacerbated by mass broadcasting and media conditioning. The cloned man becomes a symbol of the homogenization of society, where individuality is subordinated to predefined models imposed by the media.

A plush sheep placed on a table next to the television reinforces this analogy, reminding us that the masses, often represented by sheep, are easily manipulated and prone to follow dominant trends without critical thinking. The wooden table, with its classic design, contrasts with the modernity of the television, highlighting the intersection between old values and modern technologies.

Finally, the pack of Gitanes cigarettes placed on the table, a symbol of rebellion and nonconformity in the collective imagination, becomes here an ironic artifact, evoking a rebellion that, in the era of mass television and cloning, seems trivial and futile.

Hello Dolly TV is a work rich in symbols, using black humor and the repurposing of objects to deliver a biting critique of contemporary society. Stellest questions the media’s ability to shape minds and homogenize behaviors while anticipating a future where technology could dehumanize individuals by turning them into mere passive receivers of information. This sculpture, both playful and unsettling, invites us to reflect on our place in a world increasingly dominated by machines and images.

This sculpture, created in Candes Saint Martin with the collaboration of physicist-artist Bernard Gitton, combines elements of popular culture and everyday objects, transformed into critical symbols of an era marked by the industrialization of knowledge and the endless repetition of images. The central piece, an old yellow Bakelite television from the 1960s, stands as a relic from a time when technology was still perceived as a promise of a bright future. However, this television, now defective and obsolete, becomes a dystopian vehicle: the images it broadcasts are endless, creating a hypnotic loop that simulates the passive and numbing experience of media consumption.

In front of this screen, a dilapidated lounge chair, covered in drippings à la Jackson Pollock, suggests a human presence reduced to the state of a passive spectator. The paint flowing on the chair recalls both free artistic expression and the underlying chaos of modernity, contrasting with the control and repetition symbolized by the television.

The polyurethane head of a “pre-cloned” man attached to the chair’s back is a direct nod to the landmark event of the first sheep cloning, Dolly. This reference to cloning is not only biological but also ideological: the work denounces the standardization of thoughts and behaviors, a phenomenon exacerbated by mass broadcasting and media conditioning. The cloned man becomes a symbol of the homogenization of society, where individuality is subordinated to predefined models imposed by the media.

A plush sheep placed on a table next to the television reinforces this analogy, reminding us that the masses, often represented by sheep, are easily manipulated and prone to follow dominant trends without critical thinking. The wooden table, with its classic design, contrasts with the modernity of the television, highlighting the intersection between old values and modern technologies.

Finally, the pack of Gitanes cigarettes placed on the table, a symbol of rebellion and nonconformity in the collective imagination, becomes here an ironic artifact, evoking a rebellion that, in the era of mass television and cloning, seems trivial and futile.

Hello Dolly TV is a work rich in symbols, using black humor and the repurposing of objects to deliver a biting critique of contemporary society. Stellest questions the media’s ability to shape minds and homogenize behaviors while anticipating a future where technology could dehumanize individuals by turning them into mere passive receivers of information. This sculpture, both playful and unsettling, invites us to reflect on our place in a world increasingly dominated by machines and images.

Green Babies Machine

The sculpture Green Babies Machine by Patrice Stellest is a work oscillating between the absurd and the prophetic, an artistic object that seeks to be both critical and utopian. Inspired by a trivial moment—the sight of a vibrator outside an exotic supermarket—this creation takes shape in the artist’s imagination as an ironic and provocative response to the global ecological crisis.

This machine, the result of a collaboration with Martin Buller and Markus Odermatt, both possessing technical know-how inherited from the masters of Swiss mechanics, serves as a symbol of industrialization redirected towards an ecological goal. Assembled with diverse materials, the sculpture evokes mechanisms that are both rudimentary and complex, reminiscent of the kinetic works of Jean Tinguely, the spiritual mentor of one of the collaborators. The references to Tinguely are palpable in the very structure of the work, which seems fragile, rickety, yet paradoxically functional in its absurdity.

The elements that make up Green Babies Machine—a wheel, a bell, stylized horns, and a phallic object—are everyday items repurposed from their original use to become the gears of a fantastical machine. In Stellest’s mind, this machine is capable of producing “green babies,” a metaphor for a future eco-conscious generation, a condition sine qua non for the planet’s survival.

The apparent absurdity of the work masks a deeper reflection on uncontrolled industrialization and its consequences. The choice of elements and their arrangement creates a tension between humor and gravity, between play and warning. Stellest plays with contrasts, creating a gap between the playful aspect of the sculpture and the seriousness of its ecological message. The creative process, blending chance, serendipity, and collaboration, reflects Stellest’s approach, where art must be a collective adventure, open to the unexpected and interdisciplinary.

In sum, Green Babies Machine is not just a sculpture; it is a biting satire of our time, a manifesto for an “ecological baby boom” that could give the planet a chance to survive. By channeling his humor, his sense of repurposing, and his passion for mechanisms, Stellest delivers a work that makes us reflect on the future of our world while gently mocking it.

This machine, the result of a collaboration with Martin Buller and Markus Odermatt, both possessing technical know-how inherited from the masters of Swiss mechanics, serves as a symbol of industrialization redirected towards an ecological goal. Assembled with diverse materials, the sculpture evokes mechanisms that are both rudimentary and complex, reminiscent of the kinetic works of Jean Tinguely, the spiritual mentor of one of the collaborators. The references to Tinguely are palpable in the very structure of the work, which seems fragile, rickety, yet paradoxically functional in its absurdity.

The elements that make up Green Babies Machine—a wheel, a bell, stylized horns, and a phallic object—are everyday items repurposed from their original use to become the gears of a fantastical machine. In Stellest’s mind, this machine is capable of producing “green babies,” a metaphor for a future eco-conscious generation, a condition sine qua non for the planet’s survival.

The apparent absurdity of the work masks a deeper reflection on uncontrolled industrialization and its consequences. The choice of elements and their arrangement creates a tension between humor and gravity, between play and warning. Stellest plays with contrasts, creating a gap between the playful aspect of the sculpture and the seriousness of its ecological message. The creative process, blending chance, serendipity, and collaboration, reflects Stellest’s approach, where art must be a collective adventure, open to the unexpected and interdisciplinary.

In sum, Green Babies Machine is not just a sculpture; it is a biting satire of our time, a manifesto for an “ecological baby boom” that could give the planet a chance to survive. By channeling his humor, his sense of repurposing, and his passion for mechanisms, Stellest delivers a work that makes us reflect on the future of our world while gently mocking it.

Starman

Starman by Patrice Stellest is far more than just a sculpture; it is a powerful allegory of the profound connection between earth, sky, and humanity. Standing proudly with its slender silhouette, arms outstretched to the sky, the Starman embodies the mediation between the universe and our planet. This character, with its star-shaped head, represents the sun, the source of all life and a symbol of universal and radiant knowledge. This star is more than just an ornament; it is a constant reminder of our intrinsic link with the cosmos.

Beyond its iconic form, Starman is a cosmic figure that captures the energy of the universe and redirects it toward the earth. The solar panels on the Starman’s shoulders absorb solar energy, a vital and renewable resource, to redistribute it on earth. This seemingly simple gesture is, in reality, a powerful metaphor for universal acupuncture, an imaginary practice where cosmic energy is channeled to heal and rebalance our terrestrial ecosystem.

The Starman’s heart, which glows green, is the sculpture’s neural center. This vibrant heart symbolizes life, regeneration, and the wisdom of early peoples, who have always lived in harmony with nature. This green light is a reminder of ancestral wisdom, often forgotten, which is essential for restoring harmony between humanity and nature.

The formal simplicity of Starman is a tribute to Costa Coulentianos, Greek master sculptor and mentor to Stellest. Coulentianos, renowned for his monumental and streamlined works, taught Stellest the art of creating universal, accessible, and profound forms. The fluid and dynamic lines of the Starman, though simple, convey a complex message of interconnection and continuity between sky and earth. This streamlined aesthetic allows the work to reach a wide audience while inviting a deep reflection on our place in the universe.

The Starman, created by Stellest in the early 1980s, are emblematic figures in his work. These benevolent extraterrestrials, with their star-shaped heads, are on a mission to rid the Earth of violence and pollution. They represent a higher consciousness watching over our planet, embodying a protective and benevolent force. In 2010, Stellest featured these characters in his short film Stellest Genesis, which won awards worldwide. The film helped to further popularize the Starman and reinforce their symbolism as ambassadors of a new era of ecological awareness.

The choice of the name “Starman” is also a tribute to David Bowie, whose eponymous song evokes a mystical figure from the stars, bearing a message of hope and transformation. By adopting this name, Stellest weaves a link between music, art, and science fiction, integrating his work into a cultural continuity where art becomes a vector of social and spiritual change.

Starman is not just a sculpture but a call to humanity to reconnect with its natural roots and remember that its survival depends on its ability to live in harmony with the universe. Through this work, Stellest reminds us all that we are connected and that every gesture, every action, counts in preserving our planet. With its aesthetics, spirituality, and ecological commitment, Starman presents itself as a major work, a milestone in Stellest’s quest for an art that goes beyond mere contemplation to become a catalyst for transformation and reflection.

Beyond its iconic form, Starman is a cosmic figure that captures the energy of the universe and redirects it toward the earth. The solar panels on the Starman’s shoulders absorb solar energy, a vital and renewable resource, to redistribute it on earth. This seemingly simple gesture is, in reality, a powerful metaphor for universal acupuncture, an imaginary practice where cosmic energy is channeled to heal and rebalance our terrestrial ecosystem.

The Starman’s heart, which glows green, is the sculpture’s neural center. This vibrant heart symbolizes life, regeneration, and the wisdom of early peoples, who have always lived in harmony with nature. This green light is a reminder of ancestral wisdom, often forgotten, which is essential for restoring harmony between humanity and nature.

The formal simplicity of Starman is a tribute to Costa Coulentianos, Greek master sculptor and mentor to Stellest. Coulentianos, renowned for his monumental and streamlined works, taught Stellest the art of creating universal, accessible, and profound forms. The fluid and dynamic lines of the Starman, though simple, convey a complex message of interconnection and continuity between sky and earth. This streamlined aesthetic allows the work to reach a wide audience while inviting a deep reflection on our place in the universe.

The Starman, created by Stellest in the early 1980s, are emblematic figures in his work. These benevolent extraterrestrials, with their star-shaped heads, are on a mission to rid the Earth of violence and pollution. They represent a higher consciousness watching over our planet, embodying a protective and benevolent force. In 2010, Stellest featured these characters in his short film Stellest Genesis, which won awards worldwide. The film helped to further popularize the Starman and reinforce their symbolism as ambassadors of a new era of ecological awareness.

The choice of the name “Starman” is also a tribute to David Bowie, whose eponymous song evokes a mystical figure from the stars, bearing a message of hope and transformation. By adopting this name, Stellest weaves a link between music, art, and science fiction, integrating his work into a cultural continuity where art becomes a vector of social and spiritual change.

Starman is not just a sculpture but a call to humanity to reconnect with its natural roots and remember that its survival depends on its ability to live in harmony with the universe. Through this work, Stellest reminds us all that we are connected and that every gesture, every action, counts in preserving our planet. With its aesthetics, spirituality, and ecological commitment, Starman presents itself as a major work, a milestone in Stellest’s quest for an art that goes beyond mere contemplation to become a catalyst for transformation and reflection.

Weather Clock

Weather Clock by Patrice Stellest embodies a subtle balance between art and technology, designed as a mechanism for environmental vigilance and awareness of climate change. This monumental sculpture, while being strikingly simple in form, stands as an eloquent symbol of our fragile relationship with nature. Its fluid and streamlined shapes evoke iconic modernist sculptures, recalling influences such as those of Constantin Brâncuși, where pure and abstract form carries universal meaning. But beyond aesthetics, Weather Clock is a deeply interactive work, engaging viewers and the environments in which it is installed.

The conceptual core of the sculpture is based on constant interaction with the climate. Through its pendulum connected to a global network of meteorological databases, Weather Clock acts as an ecological sentinel. The pendulum, visible in close-up, embodies both the delicacy and instability of climate equilibrium. As long as temperatures remain in line with seasonal averages, it oscillates peacefully, bathed in a green glow, a symbol of nature in its balanced state.

This simple oscillation reveals the continuous resonance between the universe and the earth, a silent dialogue between humanity and natural forces that Weather Clock amplifies.

However, this harmony is fragile. When a climatic anomaly occurs—temperatures exceeding seasonal norms—the pendulum stops swinging. This immobilization marks a symbolic rupture with the natural balance, as the green glow turns red, a visual and poetic alarm that immediately engages the viewer. This sudden stop and change of light are not merely factual data but a universal message about the need for immediate action against climate change.

Every day at 8 p.m., Weather Clock delivers a daily assessment. If temperatures have remained within normal ranges, a bright green laser beam shoots from the top of the sculpture, projecting a light of life, hope, and continuity into the sky. Conversely, if temperatures have exceeded normal thresholds, a red beam cuts through the sky, a striking visual marker of climate disruption.

This play of light transforms the work into a cosmic and ecological clock, reminding humanity that time is running out, that resources are depleting, and that action is urgent. The very name, Weather Clock, resonates as an urgency, where every second counts.

In full alignment with his commitment to art with nature, Stellest has equipped this sculpture with solar panels, thus integrating a sustainable and ethical dimension to his creation. Weather Clock feeds on sunlight, the same energy source it monitors, further reinforcing the unity between art, science, and the environment. This energy self-sufficiency is a reminder that solutions exist and that technology, when used wisely, can harmonize the relationship between humanity and the planet.

But more than a simple sculpture, Weather Clock embodies the concept of universal acupuncture dear to Stellest. Placed in cities or villages, this sculpture becomes a visual marker, a silent guardian, directly challenging passersby on the ecological urgency. Each Weather Clock is an energy point, a constant signal that art can be a vector of collective consciousness. In its formal elegance and technological complexity, the work reveals that time is not infinite and that our survival depends on our ability to respect and preserve this fragile balance.

Thus, Weather Clock by Stellest is both an object of contemplation and action, a work where visual beauty is combined with a clear environmental mission. Through its sophisticated design and symbolism, it becomes a timeless monument, where art and technology unite to awaken consciousness and remind us, with every oscillation, of the precariousness of our environment and the urgency to protect it.

The conceptual core of the sculpture is based on constant interaction with the climate. Through its pendulum connected to a global network of meteorological databases, Weather Clock acts as an ecological sentinel. The pendulum, visible in close-up, embodies both the delicacy and instability of climate equilibrium. As long as temperatures remain in line with seasonal averages, it oscillates peacefully, bathed in a green glow, a symbol of nature in its balanced state.

This simple oscillation reveals the continuous resonance between the universe and the earth, a silent dialogue between humanity and natural forces that Weather Clock amplifies.

However, this harmony is fragile. When a climatic anomaly occurs—temperatures exceeding seasonal norms—the pendulum stops swinging. This immobilization marks a symbolic rupture with the natural balance, as the green glow turns red, a visual and poetic alarm that immediately engages the viewer. This sudden stop and change of light are not merely factual data but a universal message about the need for immediate action against climate change.

Every day at 8 p.m., Weather Clock delivers a daily assessment. If temperatures have remained within normal ranges, a bright green laser beam shoots from the top of the sculpture, projecting a light of life, hope, and continuity into the sky. Conversely, if temperatures have exceeded normal thresholds, a red beam cuts through the sky, a striking visual marker of climate disruption.

This play of light transforms the work into a cosmic and ecological clock, reminding humanity that time is running out, that resources are depleting, and that action is urgent. The very name, Weather Clock, resonates as an urgency, where every second counts.

In full alignment with his commitment to art with nature, Stellest has equipped this sculpture with solar panels, thus integrating a sustainable and ethical dimension to his creation. Weather Clock feeds on sunlight, the same energy source it monitors, further reinforcing the unity between art, science, and the environment. This energy self-sufficiency is a reminder that solutions exist and that technology, when used wisely, can harmonize the relationship between humanity and the planet.

But more than a simple sculpture, Weather Clock embodies the concept of universal acupuncture dear to Stellest. Placed in cities or villages, this sculpture becomes a visual marker, a silent guardian, directly challenging passersby on the ecological urgency. Each Weather Clock is an energy point, a constant signal that art can be a vector of collective consciousness. In its formal elegance and technological complexity, the work reveals that time is not infinite and that our survival depends on our ability to respect and preserve this fragile balance.

Thus, Weather Clock by Stellest is both an object of contemplation and action, a work where visual beauty is combined with a clear environmental mission. Through its sophisticated design and symbolism, it becomes a timeless monument, where art and technology unite to awaken consciousness and remind us, with every oscillation, of the precariousness of our environment and the urgency to protect it.